A collaborative research effort between the University of Nottingham in the UK and the University of Ulm in Germany has unveiled a new hybrid state of matter that straddles the line between solid and liquid. This groundbreaking discovery could pave the way for advancements in catalysis and other thermally-activated processes.

Traditionally, the transition from liquid to solid is understood as a clear shift where atoms within a substance move from a random arrangement to an ordered crystalline structure. Yet, researchers have found that this simplification does not capture the full complexity of atomic behavior. The team, led by Andrei Khlobystov from Nottingham, utilized advanced microscopy techniques to investigate melted metal nanoparticles, revealing a more nuanced interaction between solid and liquid phases.

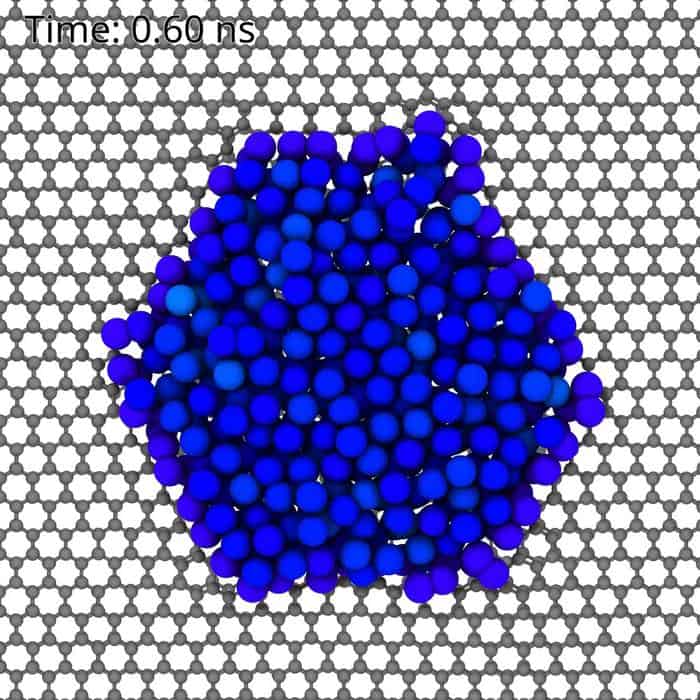

Using spherical and chromatic aberration-corrected high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (Cc/Cs-corrected HRTEM) at the low-voltage SALVE instrument in Ulm, the researchers studied nanoparticles made of metals such as platinum, gold, and palladium that were deposited on a thin layer of graphene. This carbon-based material served as a support for heating the particles, allowing for precise observations of atomic behavior at elevated temperatures.

As the nanoparticles melted, the expected rapid movement of atoms occurred. However, the researchers were surprised to find that some atoms remained stationary, binding strongly to defects in the graphene support. This finding was crucial; it indicated that the number and position of these stationary atoms significantly influenced the solidification process.

Khlobystov explained the implications of these findings, stating, “When the stationary atoms are few in number, a crystal forms directly from the liquid and grows until the entire particle solidifies. When their numbers increase, crystallization cannot occur, and no crystals form.” This unique state of matter features atoms in motion within the liquid droplet while those forming a confinement ring remain still, even at temperatures below the freezing point of the liquid.

The Cc/Cs-corrected HRTEM technique was chosen specifically for its ability to minimize aberrations, allowing the researchers to resolve individual atoms in their images. Khlobystov noted that the ability to control both the energy of the electron beam and the sample temperature using MEMS-heated chip technology enables the investigation of metal samples at temperatures up to 800 °C without losing atomic resolution.

This unprecedented level of detail provides a unique opportunity to study atomic behavior during crystallization while manipulating the environment around the metal particles. The research team initially embarked on this project while exploring 1-2 nm metal particles for catalysis, funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC).

Khlobystov elaborated on the study’s significance, stating, “We suspected that the interplay between vacancy defects in the support and the sample temperature creates a powerful mechanism for controlling the size and structure of the metal particles.” Their findings have unveiled the fundamental mechanisms behind this process with atomic precision.

Conducting these experiments posed several challenges, including the identification of a thin, robust, and thermally conductive support material. Graphene emerged as a suitable candidate, fulfilling all necessary criteria. The team also worked to control the defect sites surrounding each particle, utilizing the electron beam not merely for imaging but also to modify the environment by creating defects.

Looking ahead, the researchers express interest in harnessing this new state of matter for catalysis applications. Khlobystov emphasized the need for enhanced control over defect production and its scalability in future experiments. Additionally, they aim to image the corralled particles in a gas environment to better understand how reaction conditions influence this phenomenon, as the current measurements were conducted in a vacuum.

This research, published in ACS Nano, marks a significant step forward in our understanding of the complex behaviors of matter at the atomic level. The implications of these findings could resonate across various fields, particularly in the development of new catalytic processes and materials.