New research has uncovered a significant aspect of kinase inhibitors, revealing that these drugs, designed primarily to block enzyme activity, can also accelerate the degradation of their target proteins. The study, led by the CeMM Research Center for Molecular Medicine in Vienna, together with the AITHYRA Institute for Artificial Intelligence in Biomedicine and the Institute for Research in Biomedicine in Barcelona, was published in the journal Nature.

Researchers examined a library of 1,570 inhibitors across 98 kinases, finding that 232 compounds reduced the levels of at least one kinase, impacting 66 different kinases in total. This finding highlights a critical pharmacological feature that has been largely overlooked in the field of targeted therapy.

New Insights into Kinase Inhibitor Functionality

While the primary function of kinase inhibitors has been to block the enzymatic activity of these proteins, the new study indicates that they can also induce degradation of these targets. This phenomenon is not a rare occurrence but appears to be a common characteristic of kinase inhibitor pharmacology.

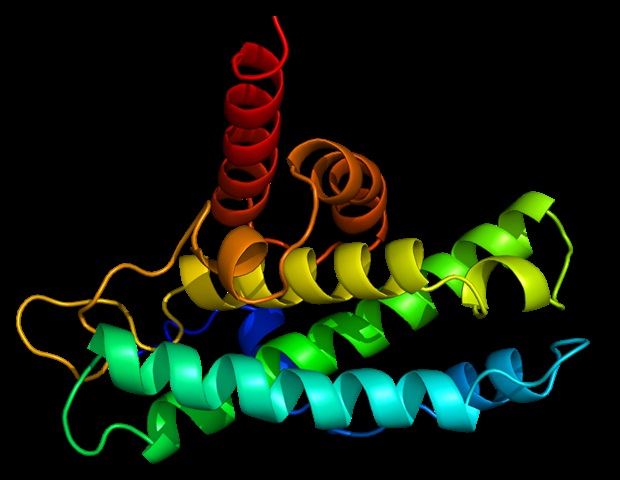

Previous suggestions hinted that inhibitors might destabilize their targets, but the full extent and mechanisms involved were unclear. The research team systematically profiled the interactions between inhibitors and kinases, uncovering a shared principle: inhibitors shift kinases into altered states, making them unstable and more susceptible to degradation by the cell’s proteolytic systems.

Natalie Scholes, a senior postdoctoral researcher at CeMM and the first author of the study, stated, “Our data show that small molecules don’t just block kinase activity; they can shift proteins into conformations that the cell recognizes as unstable. That means inhibitors can double as degraders, adding a whole new layer to how these drugs work.”

Illustrating Mechanisms with Case Studies

To elucidate these mechanisms, researchers focused on three specific kinases, each demonstrating different degradation pathways. The first kinase, LYN, was rapidly eliminated once an inhibitor triggered its instability. The second, BLK, underwent degradation only after detaching from the cell membrane, facilitated by a membrane-bound protease complex. Lastly, RIPK2 was cleared from the system after forming large protein clusters, which were recognized and removed by the cell’s recycling machinery.

These case studies collectively illustrate a broader rule: inhibitors can effectively enhance existing degradation pathways, nudging kinases into unstable states that are then targeted by the cell’s quality-control systems.

Georg Winter, Director at the AITHYRA Institute and senior author of the study, emphasized the implications of these findings. “Understanding this dimension could help us design better drugs that don’t just silence kinases but remove them altogether. In some cases, it may explain unexpected effects of existing therapies.”

As the pharmaceutical industry continues to explore the potential of kinase inhibitors, this research opens up new avenues for drug development, with the possibility of creating therapies that not only inhibit but also promote the degradation of harmful proteins associated with diseases such as cancer. The findings mark a significant shift in the understanding of kinase inhibitor functionality, underscoring the need for further exploration into this multifaceted area of pharmacology.