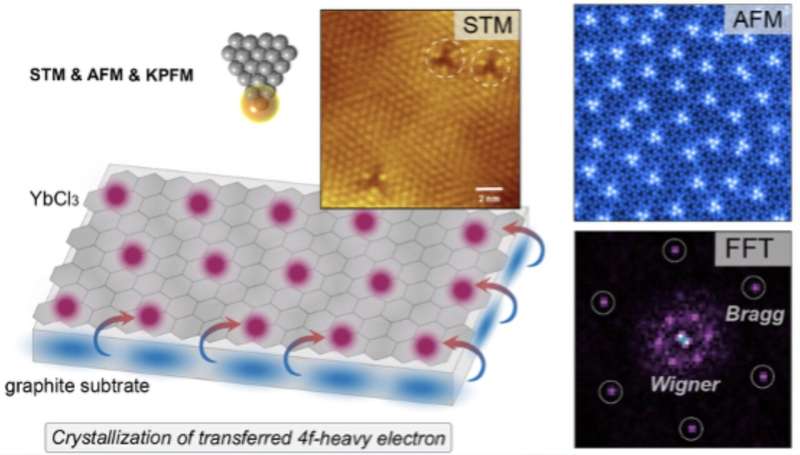

Researchers at Fudan University have made a significant breakthrough in the field of quantum materials by capturing the first images of a Wigner crystal state in a new type of two-dimensional material. This achievement, published in the journal Physical Review Letters on February 1, 2026, reveals new insights into the organization of electrons in strongly correlated systems, specifically in a monolayer of ytterbium chloride (YbCl3) situated on graphite.

Understanding Wigner Crystals

Wigner crystals are unique states of matter where electrons arrange themselves into a crystalline structure rather than moving freely. The formation of these crystals occurs due to mutual Coulomb interactions among electrons, which can be sensitive to experimental conditions. The challenge has long been to visualize and understand the internal structure of these crystals at the atomic level.

The research team, led by Chunlei Gao, employed a novel approach that involved theory-informed calculations to analyze the distribution of electric charge within their sample. Their findings indicated that approximately 0.21 e/nm² of electrons were transferred from the underlying graphite layer to the YbCl3 monolayer, creating holes in the substrate. This electron transfer resulted in the formation of interlayer excitons, which exhibit hydrogen-like Rydberg states. Co-author Zhongjie Wang remarked, “The uniqueness of the localized 4f electrons provided us with a clear window to observe it.”

Innovative Imaging Techniques

To achieve sub-unit-cell resolution images of the Wigner crystal, the researchers utilized a technique known as q-Plus atomic force microscopy (AFM). This method minimizes electrostatic distractions and allows for precise imaging of electron arrangements. “A particularly memorable moment in this exploration was during our very first AFM experiment,” said co-author Jian Shen. “As the scan progressed, the lattice of the Wigner crystal gradually came into view, and the measured electron density matched our theoretical estimates perfectly.”

The team discovered that the localized electrons exhibit a large mutual Coulomb repulsion, leading to an effective mass significantly greater than that of free electrons. Remarkably, these ‘heavy electrons’ organized themselves into a Wigner crystal phase without any external tuning, characterized by a record-high electron density and an exceptionally high melting temperature.

Gao highlighted the implications of their findings, stating, “While tremendous progress has been made in creating exotic states via electrical gating in flat-band systems like twisted graphene, our ‘charge-transfer-crystallization’ approach delivers a dilute, yet intensely correlated, 2D electron system using 4f electrons with intrinsic flat band.” This method achieves a higher carrier density of approximately 1013 /cm², compared to previous techniques that reached around 1012 /cm².

Future Research Directions

The initial results from this research open up exciting avenues for further investigation. Gao noted that the hole layer left in the graphite substrate, which is bound to the Wigner crystal, represents a coupled system that could lead to new many-body states. Future studies may explore the potential for exciton crystals or other correlated states arising from this interaction.

While current surface probes like STM and AFM provide atomic-scale resolution, they cannot access the buried hole layer within 2D materials. The team plans to employ additional experimental techniques, including transport measurements and angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES), to further examine this layer.

Additionally, the researchers aim to systematically vary the halide element in their materials, such as switching from chlorine to bromine or iodine, to tune the electron affinity and work function alignment. This strategy could uncover new quantum ground states and phase transitions in these correlated 4f electron systems.

As the field of quantum materials continues to evolve, the implications of this research are profound, potentially paving the way for new discoveries that could significantly impact the understanding of many-body physics.