An international team of researchers has successfully developed a method to precisely control the electrical charge of objects held in optical tweezers. This breakthrough, led by Scott Waitukaitis of the Institute of Science and Technology Austria, builds on an effect first observed by Nobel laureate Arthur Ashkin decades ago, and could significantly enhance the understanding of aerosols and clouds in atmospheric physics.

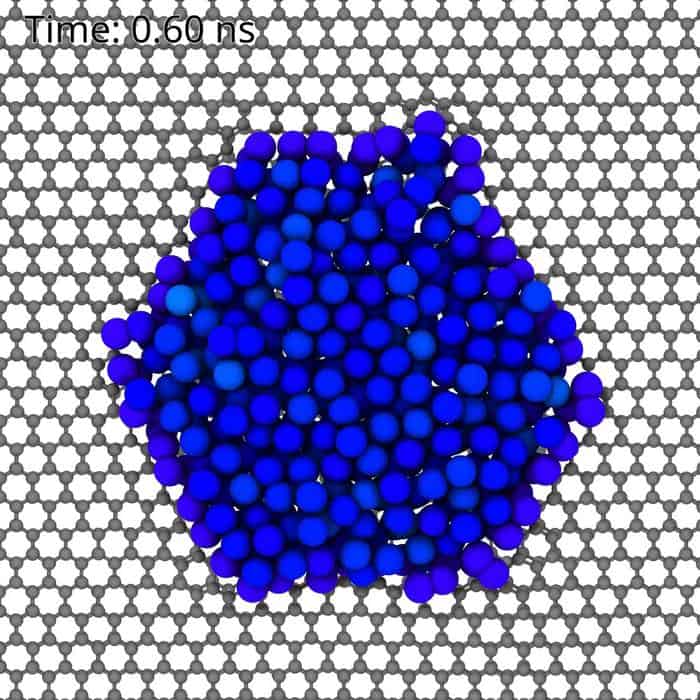

Optical tweezers, which utilize focused laser beams to trap and manipulate small particles ranging from approximately 100 nanometers to 1 micron in size, have become essential tools in various scientific disciplines, including quantum optics and biochemistry. In the 1970s, Ashkin noted that the laser light could electrically charge trapped objects, a finding that did not receive the attention it warranted at the time. “His paper didn’t get much attention, and the observation has essentially gone ignored,” Waitukaitis remarked.

Waitukaitis and his team rediscovered this electrical charging effect while investigating charge accumulation in ice crystals within clouds. During their experiments, they used micron-sized silica spheres to simulate ice, only to find that Ashkin’s charging effect interfered with their intended study. “Our goal has always been to study charged particles in air in the context of atmospheric physics – in lightning initiation or aerosols, for example,” Waitukaitis explained. Initially disheartened, the researchers soon realized they had uncovered a potentially valuable phenomenon.

Upon delving into the existing literature, they encountered Ashkin’s 1976 paper, which explained how optically trapped objects can become charged when electrons absorb two photons simultaneously. This process allows electrons to gain enough energy to escape the object, resulting in a positive charge. Although Ashkin found this discovery intriguing, he did not explore it further.

To investigate the effect in greater detail, Waitukaitis and his team modified their optical tweezers setup, integrating two copper lens holders that functioned as electrodes. This modification enabled them to apply an electric field along the axis of the opposing laser beams. If the silica sphere became charged, the electric field would cause it to vibrate, scattering a portion of the laser light back toward each lens. The researchers utilized a beam splitter to capture this scattered light, directing it to a photodiode to track the sphere’s position. By measuring the amplitude of the shaking particle, they were able to convert this data into a real-time charge measurement.

Their findings confirmed Ashkin’s hypothesis regarding the two-photon absorption process and demonstrated that the charge on a trapped object could be controlled by adjusting the laser’s intensity. Surprisingly, this effect has proven beneficial for studying charged aerosols. “We can get [an object] so charged that it shoots off little ‘microdischarges’ from its surface due to breakdown of the air around it, involving just a few or tens of electron charges at a time,” Waitukaitis noted. This capability opens new avenues for investigating electrostatic phenomena related to atmospheric particles.

The study detailing these findings has been published in Physical Review Letters, marking a significant advancement in the field of optical manipulation and atmospheric science. As researchers continue to refine this technique, the implications for understanding environmental processes and phenomena could be profound, potentially leading to new insights into climate dynamics and weather patterns.