The plight of Russian defectors continues to draw attention as many, including notable figures like Sergei Skripal, remain hidden from the Kremlin’s reach. Nearly eight years after surviving an assassination attempt in Salisbury, Skripal’s current location is reportedly New Zealand, although this may be a ruse. As the Russian government intensifies its campaign against those who betray Vladimir Putin, the risks for defectors are escalating.

Recent incidents illustrate the dangers faced by these individuals. In 2023, Maksim Kuzminov, a military helicopter pilot who defected to Ukraine, was killed in Spain just six months after urging fellow Russian pilots to switch allegiances. No suspects have been identified in his death. This is not an isolated case; historical precedents include the poisoning of former KGB agent Alexander Litvinenko in 2006, a grim reminder of the Kremlin’s resolve against traitors.

Understanding the Risks of Defection

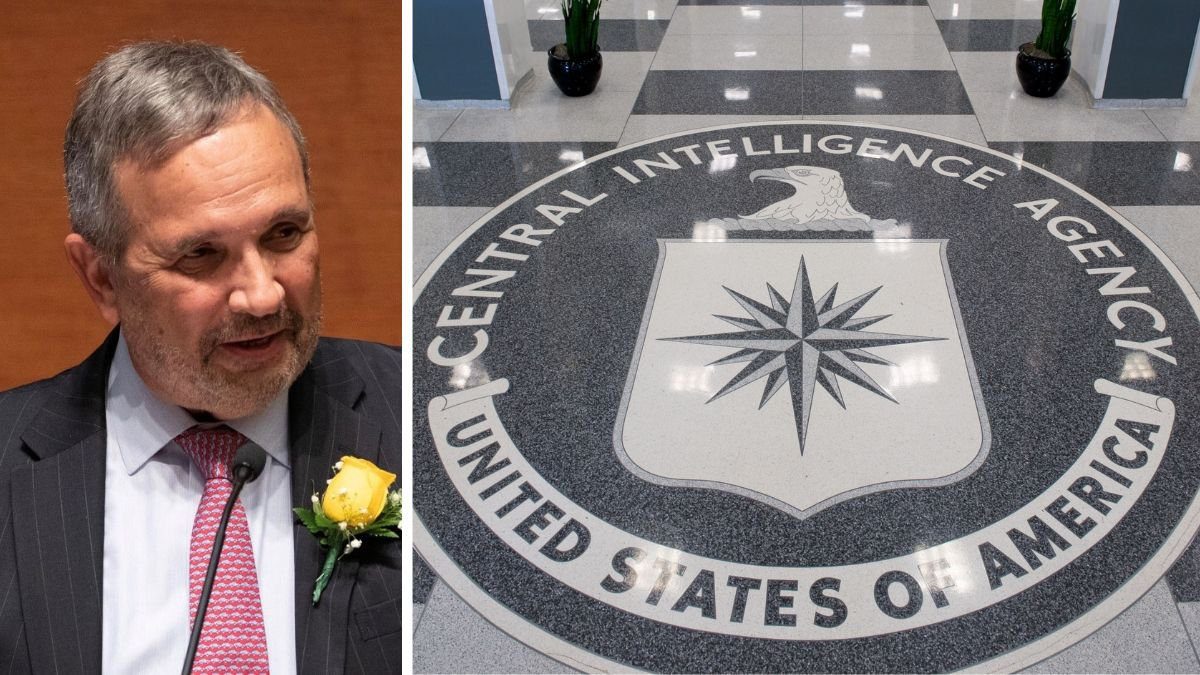

The challenges of protecting defectors from Russian reprisals are well known to Joe Augustyn, a former director of the CIA’s National Resettlement Operations Centre (NROC). This unit is responsible for facilitating new lives for foreign intelligence sources who flee to the United States. Augustyn spent nearly three years overseeing operations designed to shield these individuals from threats.

Augustyn, speaking from his home in Virginia, describes defectors as “not normal people.” He notes that they often possess A-type personalities, characterized by risk-taking and self-confidence. In his experience, most defectors are motivated by personal gain rather than ideological beliefs. “There are thousands of other spies the public never hears about, motivated simply by ego or money,” he explains.

The CIA’s approach to defectors involves comprehensive support, including new identities and relocation, but the psychological toll can be significant. For example, one defector insisted on bringing his 35 cats during a critical extraction. While such situations may seem humorous, they underline the complexities of assisting individuals who have often led secretive, high-stakes lives.

The Process of Defection

Ideally, intelligence agencies prefer to maintain their sources in the field rather than deal with defections. Spies often choose to betray their nations for various reasons, frequently driven by financial incentives or personal grievances. The CIA is legally prohibited from using coercive tactics to recruit spies, contrasting with the practices of some foreign agencies.

The consequences of exposure for defectors can be severe. Putin himself has publicly denounced traitors, branding them as “animals” or “swine.” Thus, Western intelligence agencies feel a moral obligation to exfiltrate and protect defectors from arrest or harm, not only as a humanitarian effort but also to encourage potential spies to come forward.

The CIA has the capacity to resettle up to 100 individuals annually, including their families. Although this number is rarely reached, Augustyn estimates that several hundred defectors currently reside in the United States, often feeling euphoric about their escape. However, the reality of their new lives can be stark. Many face the challenge of severing ties with their families and friends, leading to feelings of isolation.

“Your new name is Robert Smith. Your family is the Smiths… but you can never contact anyone back home,” Augustyn outlines the difficult transition for new arrivals. This reality can be particularly hard for those with young children, who must give up their social media presence entirely for safety.

The experiences of defectors like Oleg Gordievsky, a former KGB officer who provided the UK with critical intelligence, illustrate the lengths to which these individuals go to secure their safety. Gordievsky’s dramatic escape involved a covert operation where he signaled for help by carrying a specific bag to a bakery, leading to a tense exfiltration.

Despite the inherent risks, Augustyn doubts that assassination attempts, such as those on Skripal, will deter future defections. He emphasizes that these individuals are often aware of the dangers yet choose to take the plunge. Ultimately, he concludes, “I wouldn’t trust Putin, on any level, on any issue,” highlighting the complex geopolitical landscape that continues to shape the lives of defectors and their protectors.